Why We Need Smart Cities

Take a walk through almost any major city today and you’ll quickly feel both its energy and its strain. Traffic clogs the streets, public services struggle to keep pace with demand, and environmental concerns hang heavy in the air. As more of the world’s population moves into urban areas—UN estimates say nearly 70% by 2050—the question becomes urgent: how can our cities remain livable, sustainable, and efficient? The answer many experts point to is the idea of smart cities.

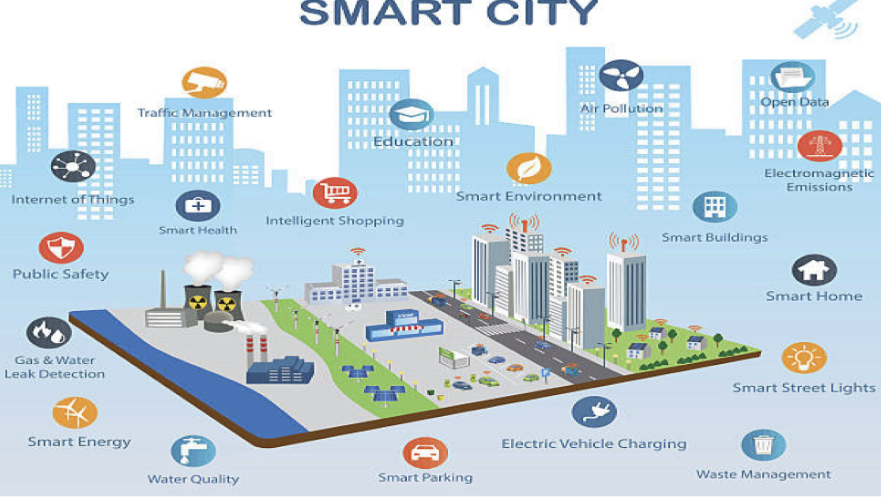

At its core, a smart city is not just about sprinkling technology on top of existing problems. It’s about rethinking how a city works, then using digital tools to make those systems more efficient, responsive, and human-centered. Imagine traffic lights that communicate with one another to reduce congestion, waste bins that signal when they’re full, or energy grids that automatically balance demand to cut costs and emissions. These are not science fiction—they’re examples already being piloted in places like Singapore, Barcelona, and Seoul.

One of the strongest arguments for smart cities is environmental. Cities account for a huge share of the world’s carbon emissions, mostly through transport and energy use. Smart solutions like electric buses coordinated by real-time demand data, or buildings that adjust heating and cooling based on occupancy, can dramatically reduce waste. If scaled globally, these changes could make cities a frontline solution in the battle against climate change.

Another need stems from public safety and health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, some cities used real-time data dashboards to track outbreaks and manage medical resources more effectively. Looking ahead, smart sensors can monitor air quality block by block, alerting residents to pollution spikes, while AI-powered analytics can help first responders get to emergencies faster. In a world of increasingly complex risks, these capabilities aren’t luxuries—they’re safeguards.

Smart cities also hold promise for equity, though only if designed with care. Digital services can make government more transparent and accessible. For example, mobile platforms can let residents report problems—like broken streetlights or unsafe intersections—directly to city hall. Public Wi-Fi and digital literacy programs can help close the gap between connected and disconnected communities. But without thoughtful policy, technology can just as easily widen divides, leaving low-income neighborhoods underserved. That’s why the “smart” in smart cities has to mean not just technological intelligence, but social intelligence too.

Of course, the path to smart cities is not without obstacles. Privacy concerns loom large, as more sensors and data collection can create risks if misused. Infrastructure upgrades cost money, and not every city has the resources of Singapore or Dubai. And citizens themselves need to be part of the design process; otherwise, “smart” projects risk solving problems nobody asked for.

Still, the need is clear. Our cities are growing, and their challenges are growing with them. Smart cities offer a way not just to manage that growth, but to turn it into an opportunity—to build places that are greener, safer, and more responsive to the people who call them home. In the end, the smartest city is one that doesn’t just use technology, but uses it to improve the everyday lives of its citizens.

Yunbo Zhu

Posted in

Posted in